Difference between revisions of "Fulton Judiciary Weaponizes Project ORCA"

(username removed) |

(username removed) |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

[[File:Full Diagram numbered.png|center|800px|elected judge]] | [[File:Full Diagram numbered.png|center|800px|elected judge]] | ||

'''Elected Judge''' | |||

[1] Campaign donors contribute money to an elected judge's campaign. | |||

2 | [2] Campaign donors then gain influence over the elected judge's decisions and, in turn, the judge caters to the desires of his or her donors. | ||

3 | [3] Elected judges use their campaign funds to influence the voters and the judge is therefore able to increase the likelihood of keeping his or her job in an election. | ||

[4] Taxpayer money funds the salary of the elected judge, though the taxpayers do not have influence over a judge's decisions because taxes are mandated by the government. | |||

<br> | |||

'''Senior Judge''' | |||

5. The writ of possession ordering that Jackson be evicted from the Property did not include his fiance and children. However, on '''January 12, 2023''', the Fulton County Sheriff Deputies used that writ of possession to remove everyone from the Property including Jackson's fiance and children. | 5. The writ of possession ordering that Jackson be evicted from the Property did not include his fiance and children. However, on '''January 12, 2023''', the Fulton County Sheriff Deputies used that writ of possession to remove everyone from the Property including Jackson's fiance and children. | ||

| Line 81: | Line 83: | ||

7. On '''February 13, 2023''', Judge Richardson voluntarily recused herself from the Quiet Title case but did NOT recuse herself from the eviction case. The Quiet Title case was re-assigned to Judge Krause upon Judge Richardson's recusal. | 7. On '''February 13, 2023''', Judge Richardson voluntarily recused herself from the Quiet Title case but did NOT recuse herself from the eviction case. The Quiet Title case was re-assigned to Judge Krause upon Judge Richardson's recusal. | ||

<br> | |||

'''Mediator''' | |||

8. Judge Krause never appointed a special master in the Quiet Title action. | 8. Judge Krause never appointed a special master in the Quiet Title action. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 92: | ||

11. On '''March 10, 2023''', Judge Ingram denied Jackson's motion to recuse Judge Leftridge from the Quiet Title action and the case was assigned back to Judge Leftridge. | 11. On '''March 10, 2023''', Judge Ingram denied Jackson's motion to recuse Judge Leftridge from the Quiet Title action and the case was assigned back to Judge Leftridge. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 18:38, 6 November 2023

Cobb Judges Abandon Constitution to Protect the Establishment

Fulton County's Project ORCA recently recruited two Cobb County Senior Judges, the Honorable G. Grant Brantley and the Honorable Adele P. Grubbs, allegedly to assist in managing the Fulton County Superior Court backlog of cases. The timing of the recruitment and their resulting rulings leave little to conjecture—Cobb Senior Judges are being used as mere cover fire for the improprieties of Fulton judges.

This article comes as an unanticipated 5th Part in a series of articles following an array of retaliatory actions of the Fulton County judiciary and law enforcement against a man not backing down to the system, Power vs. Truth. Derrick Jackson, a resident of Fulton County was robbed of his due process rights under the Constitution just days before Christmas of 2022 by Fulton County Superior Court Judge Melynee Leftridge. "After Jackson took to the media about the situation, his family was thrown out of their home located in The Country Club of the South by the Fulton County Sheriff's SCORPION Unit without a proper court order."[1][2][3][4]

Project ORCA

"On June 30, 2021, during a Fulton County Board of Commissioners meeting with the county’s mayors at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, County Manager Dick Anderson said Fulton’s court case backlog had gotten out of control."[5]

Fulton Leaders 'Brainstormed'

Just over five months later, when Fulton’s courts finally reopened, county leaders embarked on a plan to address the backlog—which, after being inventoried, totaled 148,209 open and active cases. Fulton, the state’s largest and most populous county with Georgia’s largest court case backlog, chose a name just as big for the strategy: Project Orca.[6]

According to an article written by Everett Catts of the Daily Report (available at law.com):

For Fulton, 'orca' has been synonymous with 'solution.' As of July 31, about a year and a half after launching Project Orca, the county had disposed of 108,661 cases, becoming a model for justice systems across the state and nation. In July, Fulton won one of the National Association of Counties’ Achievement Awards for its innovative methods of whittling down the backlog. In May it won an Association County Commissioners of Georgia County of Excellence Award for the same reason.[7]

So, how exactly does this Project ORCA devour cases at such a rapid pace? What is the secret? Cobb County attorney, Matthew D. McMaster, shared his opinion: "The court's due diligence is our due process. And due diligence takes time. If time is being reduced, so is due diligence and, in turn, due process. It's as simple as that."

When asked if there’s evidence proving that due process rights were being sacrificed at the hand of Project ORCA, McMaster responded: "Absolutely. The numbers don't lie.”

To his point, looking at the numbers, disposing of over 100,000 cases in a year and a half leaves little time for due process. And contributing to the atrocity, Fulton was nationally recognized "for its innovative methods of whittling down the backlog." It is clear here that, as with communism, misplaced incentives result in misbehavior—namely, abuse of power and deprivation of human rights.

Recusal Cover Fire

On April 2, 2023, Navigating Justice published an article entitled Georgia Ethics Code Does Not Apply To Fulton Judges discussing the Fulton County judiciary's refusal to recuse Judge Melynee Leftridge from presiding over multiple cases where Judge Leftridge showed clear bias, conflicts of interest, and plain incompetence. Here is a brief exert from that article:

The Courthouse Shell Game

There are two ways a judge can be recused (or "removed") from a case: (1) voluntarily and (2) involuntarily. The latter, at least in Fulton County, occurs amongst flying pigs and unicorns. Jackson's case has extracted that fact pretty clearly. On March 23, 2023, Derrick Jackson filed a Petition for Writ of Mandamus and Writ of Prohibition demanding, among other things, the recusal of the entire Fulton County Superior Court bench after two of the judges (including Judge Leftridge) failed to recuse themselves from the eviction case despite conflicts, two judges (one in the eviction case and one in the Quiet Title case) refused to recuse Judge Leftridge, and three judges (including Judge Leftridge) all refused to appoint a special master, whose appointment is mandated by Georgia law in the Quiet Title case.[8]

While Judge Melynee Leftridge has refused to recuse herself from the Jackson cases, she has since failed to appear at any hearings or rule on any motions in connection to those cases. Rather, Judge Leftridge appears to be hiding behind Project ORCA in avoidance of her duties. To that end, Cobb County Senior Judges Adele Grubbs and Grant Brantley were recruited by Project ORCA to execute Judge Leftridge's duties. As of the date of this article, Judge Leftridge still remains the assigned judge according to the Fulton County Clerk’s Office.

Cobb Leaders Rest On Their Laurels

So why would Cobb County senior judges be complicit with Fulton County's agenda? Some surface level research reveals that the start and end of the analysis lies with their personal incentives: Time & Money.

The Honorable Adele P. Grubbs

The Honorable Adele P. Grubbs (born in December of 1944) earned her law degree from Manchester University in England before she moved to the U.S., State of Georgia in 1969. Grubbs was the first woman assistant district attorney in Cobb County and was elected to the county’s Superior Court in 2000. She retired after the end of her 2016 term.

The Honorable G. Grant Brantley

The Honorable G. Grant Brantley was born in Georgia and grew up in Griffin. Brantley graduated from Emory Law School in 1964 before joining the Air Force as a judge advocate. He moved to Cobb County after his military stint and served in a variety of government positions including Cobb County Superior Court judge from 1980 to 1992. “He didn't seek reelection in 1992 because he was in the process of being nominated to the U.S. District Court by President George H. W. Bush. But the '92 election spoiled his call-up to the federal bench.”

Follow the Money

It is clear from above that both Judge Grubbs and Judge Brantley had very prominent careers on the bench and were highly regarded assets to the Cobb County justice system. However, at some point in their golden years, in their respective retirement tenures as Senior Judges, they appear to have waivered and fallen from their pedestal foundations built on principles into a pool of self sabotage, like unsuspecting hobbits clasping tightly to the Ring of Power. But for what? The most obvious answer reigns supreme: Money. Understanding how judges are paid sheds more light on the matter than is palatable.

Full-Time (Salaried) Elected Judges

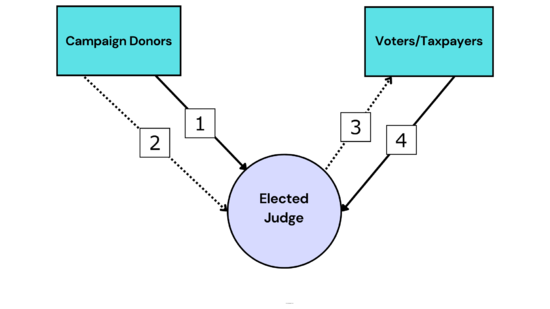

Full-time Superior Court judgeships in the State of Georgia are salaried positions that are paid with State tax dollars and often times subsidized by the county in which they preside. In Cobb County for example, Superior Court judges had salaries paid for by both State and County taxpayers totaling $200,000 annually.[9] For their pay, these "elected" officials work not less than a 40-hour workweek presiding over matters within their respective jurisdictions. Those judges serve four year terms and must be re-elected by a majority of the voters within their county if they wish to remain on the bench. Thus, their job depends on the voters and, in turn, campaign donations. The end result: Full-Time elected Superior Court judges cater to their campaign donors. In other words, campaign donors and political supporters get preferential treatment and favorable results in cases regardless of the actual facts. The following chart illustrates how campaign donations influence a full-time judge's decisions:

As shown above, [1] campaign donors contribute money to an elected judge's campaign, [2] campaign donors then gain influence over the elected judge's decisions and, in turn, the judge caters to the desires of his or her donors. [3] Elected judges then use their campaign funds to influence the voters and the judge is therefore able to increase the likelihood of keeping his or her job in an election. [4] Taxpayer money funds the salary of the elected judge, though the taxpayers do not have influence over a judge's decisions because taxes are mandated by the government.

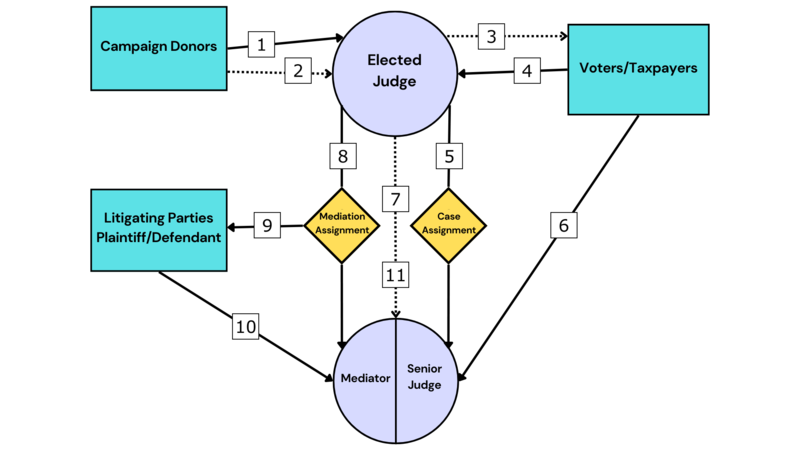

Part-Time (Hourly) Senior Judges

Part-time Senior Judges in the State of Georgia are paid hourly with tax dollars at the hourly rate equal to that of a full-time judge in the same county in which they are presiding. So, based on the $200,000 estimated Cobb County annual salary for elected judges, a Senior Judge presiding in Cobb County makes about $100 per hour. These Senior Judges obtain their respective working hours by having cases assigned to them by full-time judges. Mediator assignments are also court appointed roles that Senior Judges receive from full-time judges. And, when a Senior Judge serves as a mediator, he or she makes their money at a much higher hourly rate, usually between $150 and $350 per hour. In short, a Senior Judge's job primarily depends on the will of the full-time judge. The end result: Part-time Senior Judges cater to the desires of the assigning full-time judge. Thus, if a full-time judge wants a particular outcome in a case, the part-time Senior Judge will make it so simply to increase his or her opportunity for future appointments by that particular full-time judge.

The Big Picture

In an article published in 2022, Cobb County State Court Judge, Carl Bowers, said that when Bowers went into private practice, “Brantley told him to remember he was not just practicing law, but running a business.” Interestingly, while a judge is a government position for the purpose of serving the public, Judge Brantley treats his judgeship exactly as a business, and nothing more. The below chart illustrates exactly how the "business" of a Superior Court judge is conducted:

Elected Judge [1] Campaign donors contribute money to an elected judge's campaign.

[2] Campaign donors then gain influence over the elected judge's decisions and, in turn, the judge caters to the desires of his or her donors.

[3] Elected judges use their campaign funds to influence the voters and the judge is therefore able to increase the likelihood of keeping his or her job in an election.

[4] Taxpayer money funds the salary of the elected judge, though the taxpayers do not have influence over a judge's decisions because taxes are mandated by the government.

Senior Judge 5. The writ of possession ordering that Jackson be evicted from the Property did not include his fiance and children. However, on January 12, 2023, the Fulton County Sheriff Deputies used that writ of possession to remove everyone from the Property including Jackson's fiance and children.6. On January 31, 2023, Jackson filed a Petition to Quiet Title and Complaint for Breach of Contract against the McCrackens, which required the assigned judge to appoint a special master. That case was assigned to Judge Richardson but Judge Richardson never appointed a special master.

7. On February 13, 2023, Judge Richardson voluntarily recused herself from the Quiet Title case but did NOT recuse herself from the eviction case. The Quiet Title case was re-assigned to Judge Krause upon Judge Richardson's recusal.

Mediator 8. Judge Krause never appointed a special master in the Quiet Title action.9. On February 17, 2023, Judge Richardson denied Jackson’s motion to recuse Judge Leftridge and the eviction case was then assigned back to Judge Leftridge. Judge Krause then transferred the Quiet Title action to Judge Leftridge on February 24, 2023.

10. On March 2, 2023, Jackson's counsel motioned to recuse Judge Leftridge from the Quiet Title action and the matter was reassigned to Judge Shukura Ingram. Before Judge Leftridge signed the reassignment order as required by law, she set a hearing on the McCrackens' motion trying to stay the appointment of a special master. That hearing was set to take place on March 10, 2023 before the Honorable Judge Alford Dempsey. However, on March 9, 2023, the Court canceled that hearing in light of the resusal motion pending against Judge Leftridge.

11. On March 10, 2023, Judge Ingram denied Jackson's motion to recuse Judge Leftridge from the Quiet Title action and the case was assigned back to Judge Leftridge.

Perhaps Brantley’s many years of government employment were never about serving the public; but rather, purely for the money and personal gain. After all, one would be naive to believe that Brantley simply changed for the worse in his retirement and that this whole “chasing the almighty dollar” is a new leaf for Brantley. Tragically, who Judge Brantley is now is probably who he has always been.

Short-Sighted Swan Song

It appears that heavily distinguished and once well respected Cobb County judges have in retirement abandoned their principles and are enabling injustice at the expense of their good names. And what exactly changed (if anything) that transformed these once highly regarded Cobb County judicial leaders into mere henchmen of the establishment?

The most obvious answer prevails: How these judges make their money.

By

If you are aware of similar problems in Georgia legal matters, send the details and documents here: https://navigatingjustice.org/reporting/

November 6, 2023

See also

- Part 1: Karma prevails and Recusal Motion ensues

- Part 2: Fulton Sheriff wrongfully evicts Mother and children

- Part 3: Georgia Ethics Code Does Not Apply To Fulton Judges

- Part 4: Cobb County judge sets the record straight in Fulton, or is it all a facade?

References

- ↑ Karma prevails and Recusal Motion ensues

- ↑ Fulton Sheriff wrongfully evicts Mother and children

- ↑ Georgia Ethics Code Does Not Apply To Fulton Judges

- ↑ Cobb County judge sets the record straight in Fulton, or is it all a facade?

- ↑ How Fulton County’s Project Orca Devoured 108,661 Court Cases and Counting, by Everett Catts (August 28, 2023).

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ How Fulton County’s Project Orca Devoured 108,661 Court Cases and Counting, by Everett Catts (August 28, 2023)

- ↑ Georgia Ethics Code Does Not Apply To Fulton Judges

- ↑ Cobb Superior Court judges to get 4 percent county pay raise